Why cultural safety matters in maternity care

In Australia, the chance of dying or being unwell around the time of birth is higher for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers and babies than non-Indigenous peoples (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2020). Health professionals need to understand that racism fundamentally determines these health outcomes (Paradies et al., 2015). Institutionalised racism occurs when racism is hidden in the governance, policies, and practices of the organisation – in ways that work best for some groups and worse for others. One of the reasons Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families may avoid maternity care is that they do not feel safe or respected (Sivertsen et al., 2020). In part, this is because the western, biomedical approach to healthcare is at odds with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander holistic approaches to birth and birthing practices. These holistic approaches recognise the intricate relationships mothers and babies have to Country. There is a national drive for Birthing on Country, to provide Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families with a holistic, integrated and culturally safe model of care that supports the best start in life (Molly Wardaguga Research Centre, 2019).

Learning culturally safe practice

Recognising that institutional racism underpins Australian healthcare, has sparked new ways of teaching and learning to promote health equity and social justice. Indeed, midwives must learn to practice in culturally safe ways when working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families and communities. This requirement has been mandated by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leaders and peak professional bodies (Australian Nursing and Midwifery Council (ANMAC), 2017; Australian Health Professional Regulation Agency (AHPRA), 2018). But learning cultural safety learning is not just about understanding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture, outcomes and social determinants of health. Primarily, it is about how non-Indigenous health students grapple with institutional racism within the healthcare system and critically reflect on their role within it.

Why emotion impacts learning cultural safety

Students react in different ways when learning cultural safety content. Some may begin to adopt anti-oppressive practice quickly, while others can become defiant, or experience significant emotional adversity. Non-Indigenous students may lack knowledge of the effects of settler colonialism and/or feel that their social identity is being challenged. This may lead to emotional reactions that are complex, and often semi-conscious. As students work through these emotional experiences, protective mechanisms (such as outward displays of anger) may arise. Alternatively, students may become caught in feelings of guilt and shame (Mills and Creedy, 2019). Becoming ‘stuck’ in these emotions reinforces inertia and preserves the status quo. Staying stuck makes institutional racism difficult to address in any meaningful way. Despite the complexity of teaching and learning in cultural safety, research about students’ complex emotional reactions has been rare.

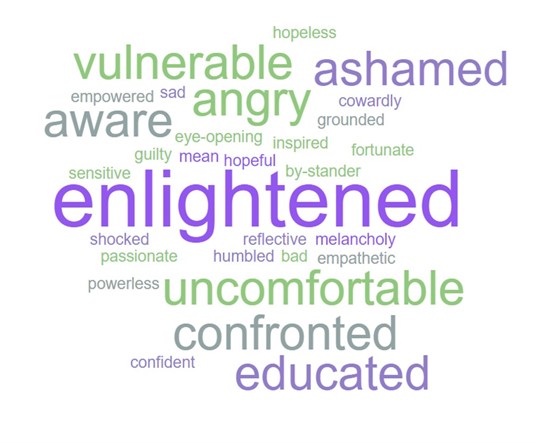

Measuring emotion

Our research team developed and tested a survey tool to understand non-Indigenous student emotional learning experiences in cultural safety education (Mills, Creedy, Sunderland & Allen, 2021). The tool, named the Student Emotional Learning in Cultural Safety Instrument (SELCSI), is First Peoples-led with two scales of measurement: witnessing and comfort. The SELCSI was tested with 109 nursing and midwifery students after finishing a semester-long cultural safety course. Our results showed that the SELCSI is a valid and reliable measure of emotion in cultural safety education. In addition, the comfort scale can be used to support students to reflect on their level of comfort with cultural safety content. For educators, the scale can be used to see how students are sitting with the content to enable them to adapt to students’ needs.

Where to from here

Understanding and measuring non-Indigenous students’ emotions when learning cultural safety will support student reflection and learning. At the same time, it will promote responsive and innovative approaches to cultural safety education. Significantly, measuring emotion using the SELCSI may be fundamental to culturally safe health practice. Cultural safety is required to achieve health equity for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

References

Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA). (2018). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Strategy – Statement of Intent. https://www.ahpra.gov.au/About-AHPRA/Aboriginal-and-Torres-Strait-Islander-Health-Strategy/Statement-of-intent.aspx

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2020). Australia’s Mothers and Babies 2018 – In Brief. Canberra: AIHW.

Australian Nursing and Midwifery Accreditation Council (ANMAC). (2017). Enrolled Nurse Accreditation Standards 2017. https://www.anmac.org.au/sites/default/files/documents/ANMAC_EN_Standards_web.pdf

Mills, K., & Creedy, D. (2019). The ‘Pedagogy of discomfort’: A qualitative exploration of non-indigenous student learning in a First Peoples health course. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2019.16

Mills, K., Creedy, D. K., Sunderland, N., & Allen, J. (2021). Examining the transformative potential of emotion in education: A new measure of nursing and midwifery students’ emotional learning in first peoples’ cultural safety. Nurse Education Today, 104854. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2021.104854

Molly Wardaguga Research Centre. (2019). Birthing on Country. Retrieved from www.birthingoncountry.com

Paradies, Y., Ben, J., Denson, N., Elias, A., Priest, N., Pieterse, A., Gee, G., 2015. Racism as a determinant of health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 10 (9), e0138511.

Sivertsen, N., Anikeeva, O., Deverix, J., & Grant, J. (2020). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander family access to continuity of health care services in the first 1000 days of life: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Health Serv Res, 20(1), 829. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05673-w